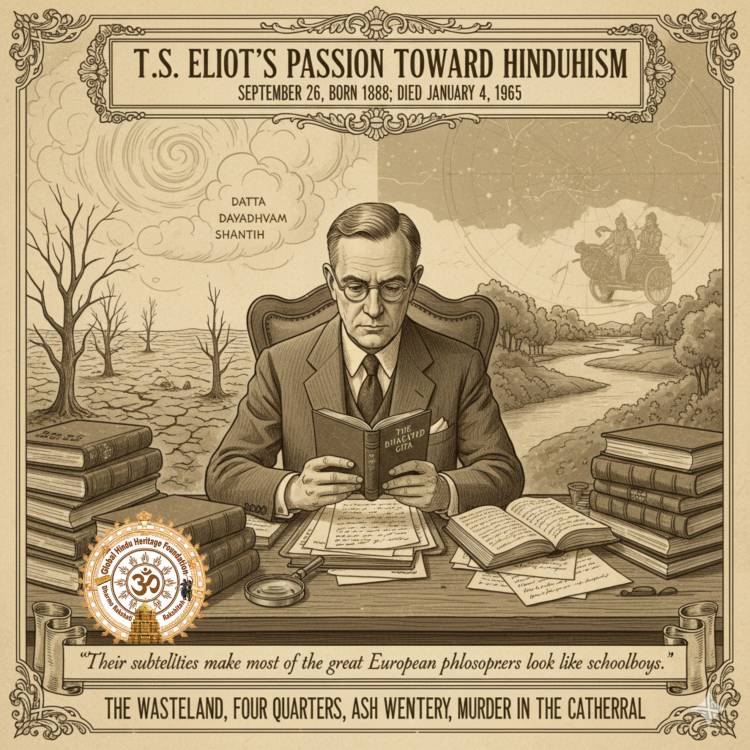

[GHHF] T.S. Elliot’s Passion toward Hinduism

September 26, Born 1888, S Eliot; Died January 4, 1965

September 26, Born 1888, S Eliot; Died January 4, 1965

T. S. (Thomas Stearns) Eliot (1888-1965), American English, Harvard-educated poet, playwright, and literary critic, was a leader of the modernist movement in literature.

Eliot was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1948. He drew his intellectual sustenance from the Bhagavad Gita. He considered it to be the greatest philosophical poem after Dante's Divine Comedy. (source: Resinging the Gita).

Also, he kept a copy of The Twenty-eight Upanishads in his personal library for ready reference. (Among the books from Eliot's library now in the Hayward Bequest in King's College Library is Vasudev Lazman Sastri Phansikar's The Twenty-Eight Upanishads (Bombay: Tukaram Javaji, 1906).

Inscribed on the fly-leaf is the following note: Thomas Eliot with C.R. Lanman's kindest regards and best wishes. Harvard College. May 6, 1912. At Harvard, Eliot studied Sanskrit and Pali for two years (1920-11), probably to acquaint himself with Indian philosophical texts in the original, for he later admitted that though he studied "the ancient Indian languages" and " read a little poetry," he was "chiefly interested at that time in philosophy."

As early as 1918, Eliot reviewed for The Egoist an obscure treatise on Indian philosophy, titled Brahmadarsanam or Intuition of the Absolute, by Sri Ananda Acharya.

(source: T. S. Eliot Vedanta and Buddhism - By P. S. Sri, pp. 10-11 and 126).

Eliot wrote in 1933:

"Their (Indian philosophers') subtleties make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys."

An unexpected remark from a man who devoted his career to a defense of the European tradition and who had studied under Bertrand Russell, Josiah Royce, R. G. Collingwood, Harold Joachim, and Henri Bergson

Consequent on his early exposure to Indic thought through Edwin Arnold's The Light of Asia, whether by chance or by personal bidding, Eliot resolved to go on a passage to India ("reason's early paradise" in the words of Whitman) and imbibe deep the native spring of the Vedas.

The moral implications of the doctrine of Karma find a powerful evocation in the Murder in the Cathedral. The concept of true action, which is not concerned with the fruits of action, is a profound insight from the Bhagavad Gita.

(source: After Strange Gods - By T. S. Eliot and The Making of Eliot - hindu.com). For more, refer to The Hidden Advantage of Tradition: On the Significance of T. S. Eliot's Indic Studies.

Over and over again, whether in The Wasteland, Four Quarters, Ash Wednesday, or Murder in the Cathedral, the influence of Indian philosophy and mysticism on him is clearly noticeable.

In his poem 'The Dry Salvages' Eliot reflects on Lord Krishna's meaning:

"I sometimes wonder if that is what Krishna meant-

Among other things, or one way of putting the same thing:

That the future is a faded song, a Royal Rose, or a lavender spray

Of wistful regret for those who are not yet here to regret."

He mentioned "Time the destroyer" (section 2), then summarized one of Krishna's points:

"And do not think of the fruit of action.

Fare forward...

So Krishna, as when he admonished Arjuna

On the field of battle,

Not fare well,

But fare forward voyagers (section 3).

He refers to the Gita's central doctrine of nishkama karma, 'selfless endeavor.' He also discusses the decomposition of modern civilization, the lack of conviction and direction, and the confusion and meaninglessness of modern consciousness in his poem "The Wasteland."

As Prof. Philip R. Headings has remarked in his study of the poet, "No serious student of Eliot's poetry can afford to ignore his early and continued interest in the Bhagavad Gita."

Eliot familiarized himself with parts of the Vedas and the Upanishads during the course of his graduate studies. He drew upon this knowledge as background for certain poetic and dramatic situations in his work.

Of all the American writers who have drawn upon Indian sources, T. S. Eliot was one who knew his sources firsthand and not merely through translations by Western Orientalists.

Eliot perceived the Indian tradition in poetry and philosophy as a vital force in world culture, and he appropriated elements that were suitable for his own themes and purposes. The theme of draught and sterility in The Waste Land seems to be inspired by the Vedic myth of Indra slaying Vritra, who had held up the waters in the heavens. In the "What the Thunder Said" section of The Waste Land, we have the following lines:

"Ganga was sunken and the limp leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant,

The jungle crouched, humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder."

Then follows a sequential use of DA-Datta. What have we given? DA-Dayadhvam and DA-Damayata, which, as he explains in the Notes, are taken from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The last line contains the phrase "Shantih Shanthi Shanthi."

He says: "Two years spent in the study of Sanskrit under Charles Lanman, and a year in the mazes of Patanjali's metaphysics under the guidance of James Woods, left me in a state of enlightened mystification. A good half of the effort of understanding what the Indian philosophers were after - and their subtleties make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys - lay in trying to erase from my mind all the categories and kinds of distinction common to European philosophy was hardly better than an obstacle.

"In the literature of Asia is a great poetry. There is also profound wisdom and some very difficult metaphysics...Long ago I studied the ancient Indian languages, and while I was chiefly interested at that time in philosophy, I read little poetry too; and I know that my own poetry shows the influence of Indian thought and sensibility."

On the influence of influence of the Bhagavad Gita, he felt "very thankful for having had the opportunity to study the Bhagavad Gita and the religious and philosophical beliefs, so different from (my) own with which the Bhagavad Gita is informed."

(source: India in the American Mind - By B. G. Gokhale p. 120-21) India and World Civilization By D. P. Singhal, Pan Macmillan Limited. 1993. Pg. 60-62).

Preceding this word and yet in the same context is the threefold message of the thunder— Da Da Da, which Eliot drew from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (5,1).

These three words stand for Datta, Dayadhvam, Damyata, respectively meaning "Give, Sympathize, Control." In the Upanishadic context, the meaning is symbolic. The terms summarize Prajapati's teaching to three kinds of his disciples: gods, humans, and demons. After their formal education, they ask him what kind of virtues they should obtain to lead a meaningful life, and Prajapati responds with the same word, Da, three times each with a different meaning. To the gods, it means Damyata -control yourself/ restraint; to the men, it conveys Datta -give in/ charity; and to the demons, it suggests Dayadhvam -be compassionate. These words, along with shantih, at the end of the poem have elicited numerous interpretations.

Eliot’s prescription for a new dawn is given in Part V — “What the Thunder Said.”

“Ganga was sunken, and the limp (wilted) leaves

Waited for rain, while the black clouds

Gathered far distant, over Himavant.

The jungle crouched (bent), humped in silence.

Then spoke the thunder

Urgent support needed for Bangladesh Hindus

Urgent support needed for Bangladesh Hindus