[GHHF] International Day of Yoga:Who Established the Yoga roots in USA? – Part 1

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi during his address to UN General Assembly in September 2014, had asked world leaders to adopt an international Yoga Day, saying “Yoga embodies unity of mind and body; thought and action; restraint and fulfillment; harmony between man and nature; a holistic approach to health and wellbeing. Yoga is not just about exercise; it is a way to discover the sense of oneness with yourself, the world and the nature. ” On December 11, 2014, the 193-member UN General Assembly adopted a resolution by consensus, proclaiming June 21 as ‘International Day of Yoga’. The resolution was introduced by India’s Ambassador to the UN and had 175 UN members, including five permanent members of the UN Security Council, as co-sponsors.

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi during his address to UN General Assembly in September 2014, had asked world leaders to adopt an international Yoga Day, saying “Yoga embodies unity of mind and body; thought and action; restraint and fulfillment; harmony between man and nature; a holistic approach to health and wellbeing. Yoga is not just about exercise; it is a way to discover the sense of oneness with yourself, the world and the nature. ” On December 11, 2014, the 193-member UN General Assembly adopted a resolution by consensus, proclaiming June 21 as ‘International Day of Yoga’. The resolution was introduced by India’s Ambassador to the UN and had 175 UN members, including five permanent members of the UN Security Council, as co-sponsors.

World Health Organization has also urged its member countries to help their citizens reduce physical inactivity, which is among the top ten leading causes of death worldwide, and a key risk factor for non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancer and diabetes. In fact, many Universities and Medical Hospitals have been conducting research and publishing voluminous amount of research on the effects of the physical and mental well-being of the people. UNICEF recommends that kids can practice many yoga poses without any risk and get the same benefits that adults do. These benefits include increased flexibility and fitness, mindfulness, and relaxation.

Year 2020 is even more important to celebrate the 6th International Day of Yoga because of its very nature to relax the mind, reduce the stress, boost the immune system, and improve the health benefits. Coronavirus has disrupted the routine life, curbed the movements, forced people to maintain social distance, required some people to maintain physical isolation, compelled people to work at home, cancel almost all air travel and restricted the movements causing more stress, anxiety, restlessness, agitation, irritation, and tension. Yoga comes to the rescue for those who take this rare opportunity to practice it, experience it and benefit from it.

Yoga and Meditation in USA

The popularity of Yoga is increasing year by year through the number of people practicing Yoga and the number of Yoga centers sprung up in USA. The 2016 Yoga in America Study Conducted by Yoga Journal and Yoga Alliance is a national study revealed surprising results.

Survey highlights:

- The number of American yoga practitioners has increased to over 36 million in 2016, up from 20.4 million in 2012. 28% of all Americans have participated in a yoga class at some point in their lives.

- Statista Research Development projects that total number of yoga practitioners will increase to 55 million by 2020.

- 34% of Americans say they are somewhat or very likely to practice yoga in the next 12 months equal to more than 80 million Americans. Reasons cited include flexibility, stress relief and fitness.

- 75% of all Americans agree “yoga is good for you.”

Why the popularity is increasing year by year? It appears the more stress people experience; more they turn to methods that give them peace of mind. Yoga and meditation are considered the best methods to quiet a busy mind. As one practitioner sated, “But yoga is my medication. I feel good—soul, mind, and spirit in clarity.” Josephine P. Briggs, M.D., Director of NCCIH says, “This reaffirms how important it is for NIH to rigorously study complementary health approaches and make that information easily available to consumers.”

Who sowed the seeds of Yoga in USA?

As we celebrate the sixth International Yoga Day, let us take this opportunity to trace the history of three stalwarts – Emerson, Thoreau and Whitman - who paved the way in 19th century for the present abiding interest, widespread enthusiasm, and uninhibited fascination toward yoga and meditation in USA. Then came Swami Vivekananda and Paramahansa Yogananda who popularized yoga travelling to many places all across USA. We will examine their contribution to make yoga an acceptable method of exercise in some sectors of elite community.

The roots of Yoga and Meditation can be traced to early 19th century starting around 1840s. Before Swami Vivekananda landed in the US and gave that rousing speech at the Parliament of Religions, the triad of scholars prepared the American soil to experience the benefits of yoga and meditation.Emerson, Thoreau and Whitman have sown the Oriental seed in the Occidental soil preparing for others to reap the fruits of the yield. These transcendentalists have shifted the paradigm by preparing the ground for others.

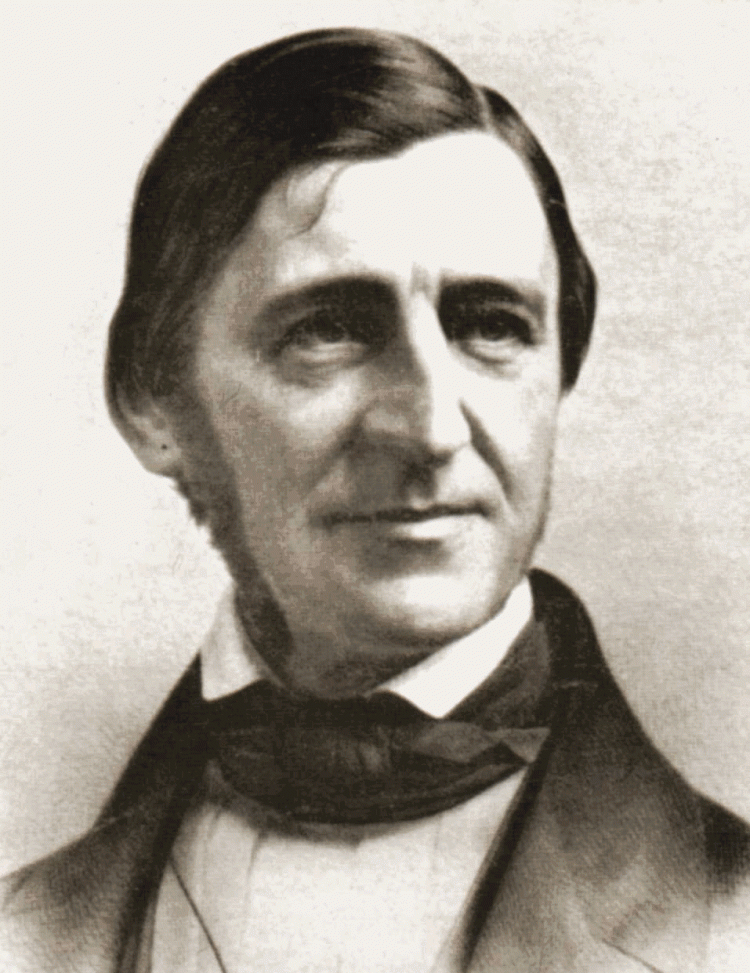

Ralph Waldo Emerson: 1803-1882

“We do not determine what we will think.” Ralph Waldo Emerson

“We do not determine what we will think.” Ralph Waldo Emerson

The groundwork for this paradigm shift had been established, however, by those Americans who were attracted to the wisdom that they found in those Hindu sacred texts that had been translated into English, some of which were available to American readers as early as the eighteenth century: texts such as the Bhagavad Gita, Laws of Manu, Bhagavad Purana, Vishnu Purana and some of the majorUpanishads. The Transcendentalist movement, consisting of such figures as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman, was deeply indebted to these texts. The Transcendentalists were, in effect, the first American Vedantists.

Emerson is considered to be the most influential author of the 19th century; his name was known far and wide. In the 1830s, Emerson had copies of the Rig Veda, the Upanishads, the Laws of Manu, the Bhagavata Purana, and his favorite Indian text, the Bhagavad Gita. “I owed a magnificent day to the Bhagavad-Gita. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.”

Repelled by the increasing materialism of the West, Emerson turned to India for solace:

"The Indian teaching, through its clouds of legends, has yet a simple and grand religion, like a queenly countenance seen through a rich veil. It teaches to speak truth, love others, and to dispose trifles. The East is grand - and makes Europe appear the land of trifles. ...all is soul and the soul is Vishnu ...cheerful and noble is the genius of this cosmogony. Hari is always gentle and serene - he translates to heaven the hunter who has accidentally shot him in his human form, he pursues his sport with boors and milkmaids at the cow pens; all his games are benevolent and he enters into flesh to relieve the burdens of the world."

Emerson, talking of the Upanishads and the Vedas, said that having read them, he could not put them away. "They haunt me. In them I have found eternal compensation, unfathomable power, unbroken peace."

His essay on “Over-Soul” published in 1841 was considered the greatest article appears to have been influenced by Vedanta and yogic experience. This term denotes the transcendence of duality, or plurality. It emphasizes the unity and oneness. It clearly described the inner experiences of mysticism. Yoga and meditation ideas are amply imbedded in this article on Over-Soul.

“… that Unity, that Over-Soul, within which every man’s particular being is contained and made one with all other… We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal One. And this deep power in which we exist, and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul. . . .

“… that Unity, that Over-Soul, within which every man’s particular being is contained and made one with all other… We live in succession, in division, in parts, in particles. Meantime within man is the soul of the whole; the wise silence; the universal beauty, to which every part and particle is equally related; the eternal One. And this deep power in which we exist, and whose beatitude is all accessible to us, is not only self-sufficing and perfect in every hour, but the act of seeing and the thing seen, the seer and the spectacle, the subject and the object, are one. We see the world piece by piece, as the sun, the moon, the animal, the tree; but the whole, of which these are the shining parts, is the soul. . . .

From within or from behind, a light shine through us upon things, and makes us aware that we are nothing, but the light is all. A man is the facade of a temple wherein all wisdom and all good abide. . . . When it breathes through his intellect, it is genius; when it breathes through his will, it is virtue; when it flows through his affection, it is love. . . .”

The concept Over-Soul is equated with Paramatma – Parama to mean super and atma to mean soul. Supreme Soul is nothing but Over-Soul. At that level Emerson observed “brief moments” that contain “more reality” than “all other experiences.”

He finds solace in the spiritual dimension of India over the materialistic West. "The Indian teaching, through its clouds of legends, has yet a simple and grand religion, like a queenly countenance seen through a rich veil. It teaches to speak truth, love others, and to dispose trifles. The East is grand - and makes Europe appear the land of trifles. ...all is soul and the soul is Vishnu ...cheerful and noble is the genius of this cosmogony. Hari is always gentle and serene - he translates to heaven the hunter who has accidentally shot him in his human form, he pursues his sport with boors and milkmaids at the cow pens; all his games are benevolent and he enters into flesh to relieve the burdens of the world."

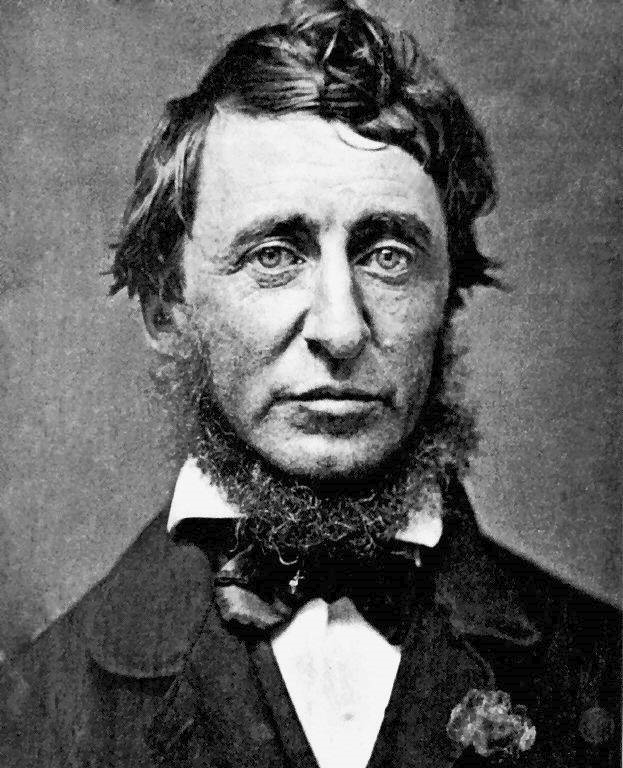

Thoreau was America’s first practicing yogi.

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) spent plenty of time during his seclusion at Walden Pond in 1847, who was probably the first to actually practice silence and yoga. Thoreau adopted an ascetic diet and spent hours, from sunrise till noon, “rapt in reverie…in undisturbed solitude and stillness,” as he put it. He didn’t do yoga poses, but his embrace of meditation, which would have been very odd in his day, is impressive. In those days no record of anyone else practicing Yoga to experience the contemplation. This interest in yoga might have been ignited after reading Manusmriti. He said that “I cannot read a single word of the Hindoos without being elevated.”

Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862) spent plenty of time during his seclusion at Walden Pond in 1847, who was probably the first to actually practice silence and yoga. Thoreau adopted an ascetic diet and spent hours, from sunrise till noon, “rapt in reverie…in undisturbed solitude and stillness,” as he put it. He didn’t do yoga poses, but his embrace of meditation, which would have been very odd in his day, is impressive. In those days no record of anyone else practicing Yoga to experience the contemplation. This interest in yoga might have been ignited after reading Manusmriti. He said that “I cannot read a single word of the Hindoos without being elevated.”

Practicing yoga faithfully for about two years at Walden and reading a number of Hindu scriptures, he wrote: “In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagavat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! There I meet the servant of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the River Ganga reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water---jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganga (Ganges)."

And” One sentence of the Gita, is worth the State of Massachusetts many times over"

The book Walden reals the passion, excitement and inspiration Thoreau derived from the Hindu sacred books. It mentions that he used to keep a copy of Bhagavad Gita on his bedside in his cabin; compared the pond with “Ganges River”; and how retreated to the pond to experience the spirit of the ascetic sages of India. He often mentioned about how Asiatic ideas had transformed him spiritually and intellectually. He even mentioned about how his spiritual ecstasy left him “daily intoxicated” with “an indescribable, infinite, all-absorbing, divine, heavenly pleasure, a sense of elevation and expansion .... I speak as a witness on the stand, and tell what I have perceived. The morning and the evening were sweet to me, and I led a life aloof from the society of men.”

Henry David Thoreau “I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a reverie, amidst the pines and hickory and the sumaches in undisturbed solitude and stillness … I realize what the Oriental mean by contemplation and the forsaking of work.” He says that the man’s close relationship with the nature would energize the spirits and heal the natural environment and help stimulate contemplation and meditation. He felt that the peace, silence, and solitude of the natural environment are essential to practice meditation. He stated that “by the time the villagers had broken their fast the morning sun had dried my house sufficiently to allow me to move in again, and my meditations were almost uninterrupted.” The he goes on to say that “Now that the cars are gone by and all the restless world with them, and the fishes in the pond no longer feel their rumbling, I am more alone than ever. For the rest of the long afternoon, perhaps, my meditations are interrupted only by the faint rattle of a carriage or team along the distant highway.”

In one of his chapter, “A Pond in the Winter,” he described how his model day would be like in winter. He reads Bhagavad Geeta after he gets up to experience that stupendous and cosmological philosophy. With that mind set, he goes to the pond where he said would meet “the servants of the Brahmin, priest of Brahma, and Vishnu and Indra who still sits in his temples on the Ganges reading the Vedas … I meet his servant come to draw the water and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

Thoreau affirmed to Harrison Blake that “to some extent and at rare intervals even I am a yogi. ”How highly Thoreau cherished the inactive life of the yoga, the contemplative life in solitude, can be illustrated by the fact that he devoted two complete chapters of Walden and parts of several others not only to extol the positive virtues of solitude and the meditative life in general, but to show in particular how he himself was a devotee of the yoga while at Walden Pond.

Thoreau embarked on his Walden experiment in the spirit of Indian asceticism. He went into seclusion not for Christian repentance but for contemplation on the very nature of himself to be released from the daily drudgery and petty daily routines. He was practicing what was prescribed in the sixth chapter of Bhagavad Gita that explains the ashtanga Yoga and the difficulties of the mind and how to gain mastery over it. In a letter written to H. G. O Blake in 1849, he remarked:

"Free in this world as the birds in the air, disengaged from every kind of chains, those who have practiced the Yoga gather in Brahmin the certain fruit of their works. Depend upon it, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. This Yogi, absorbed in contemplation, contributes in his degree to creation; he breathes a divine perfume, he heard wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him and he goes, he acts as animating original matter. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a Yogi.

"Free in this world as the birds in the air, disengaged from every kind of chains, those who have practiced the Yoga gather in Brahmin the certain fruit of their works. Depend upon it, rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. This Yogi, absorbed in contemplation, contributes in his degree to creation; he breathes a divine perfume, he heard wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him and he goes, he acts as animating original matter. To some extent, and at rare intervals, even I am a Yogi.

Thoreau read every book on Indian Philosophy available to him in those days after 1855. His praise to these books is extracted thus:

What extracts from the Vedas I have read fall on me like the light of a higher and purer luminary, which describes a loftier course through a purer stratum.

Whenever I have read any part of the Vedas, I have felt that some unearthly and unknown light illuminated me. In the great teaching of the Vedas, there is no touch of the sectarianism. It is of all ages, climes, and nationalities, and is the royal road for the attainment of the Great Knowledge.

When my imagination travels eastward and backward to those re-mote years of the gods, I seem to draw near to the habitation of the morning, and the dawn at length has a place.

Like Emerson, Thoreau had mystical experiences that Vedanta helped him to understand. "The texts were a kind of touchstone for his own.

Alan Hodder said, "He had moments of euphoria and rapture in nature, but he couldn't really explain them until he started reading the Indian material. Then he actually saw references to what he was experiencing, and he thought, 'Aha! I'm not the only one having this. There's a long tradition to it. The sacred books also taught Thoreau the important distinction between philosophical inquiry and spiritual practice. "One may discover the root of an Indian religion in his own private history," Thoreau wrote in his journal, "when, in the silent intervals of the day and night, he does sometimes inflict on himself like austerities with stern satisfaction." He may have been the first American to call himself a yogi. He even wrote to his friend about what he experiences during those intervals: “The yogin breathes a divine perfume, he hears wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him, and, united to nature, which is proper to him, he goes, he acts as animating original matter.”

How did he describe the Yogic experiences in Walden?

Thoreau practiced yoga and speaks of it in Walden in explicit terms. He even styled himself a "Yogi." In Walden he writes: "I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor." Yoga, as the Vedantist understands it, is not an esoteric practice but meditative discipline, a focusing of consciousness. It is, in the words of the Gita, a conscious endeavor to "lift the self by the self." Only by such mental discipline can one develop the intuitive faculty, which alone will ultimately take one to the deep-lying essence beneath. Thoreau writes, "By a conscious effort of mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent. We are not wholly involved in nature."

Thoreau practiced yoga and speaks of it in Walden in explicit terms. He even styled himself a "Yogi." In Walden he writes: "I know of no more encouraging fact than the unquestionable ability of man to elevate his life by a conscious endeavor." Yoga, as the Vedantist understands it, is not an esoteric practice but meditative discipline, a focusing of consciousness. It is, in the words of the Gita, a conscious endeavor to "lift the self by the self." Only by such mental discipline can one develop the intuitive faculty, which alone will ultimately take one to the deep-lying essence beneath. Thoreau writes, "By a conscious effort of mind we can stand aloof from actions and their consequences; and all things, good and bad, go by us like a torrent. We are not wholly involved in nature."

He found in the Hindu scriptures the conceptions of human life and human potential to a higher elevation. He says that there is divine within each soul and similar divinity is also found in the nature. He said on “rare intervals” his consciousness becomes unbound and experience it as a shoreless and island less ocean. Let us look at what he experiences during those rare intervals:

If with closed ears and eyes I consult consciousness for a moment, immediately are all walls and barriers dissipated, earth rolls from under me, and I float . . . in the midst of an unknown and infinite sea, or else heave and swell like a vast ocean of thought, without rock or headland, where are all riddles solved, all straight lines making there their two ends to meet, eternity and space gamboling familiarly through my depths. I am from the beginning, knowing no end, no aim. No sun illumines me, for I dissolve all lesser lights in my own intenser and steadier light. I am a restful kernel in the magazine of the universe. . .

Men are constantly dinging in my ears their fair theories and plausible solutions of the universe, but ever there is no help, and I return again to my shoreless, island less ocean. (The Selected Journals of Henry David Thoreau, ed. Carl Bode (New York: New American Library, Signet Classics, 1960): 39.)

Part 2 of the article will continue on21st

Urgent support needed for Bangladesh Hindus

Urgent support needed for Bangladesh Hindus